Beaver Tails | master index

|

"The Wonderful Beaver"

Derek Palmer © 2006  |

|

A nostalgic series of "yarns" by a retired AAC Pilot.

|

|

|

|

Chapter 1. Oh, for a Beaver! This story leads up to and describes one of the reasons why I converted on to Beavers, but does not actually feature one. All of the events I shall describe took place in what is now part of the Yemen, but used to be the Western Aden Protectorate (WAP), a British controlled area until 1969. The WAP covered approximately 10,000 square miles in the South West corner of the Saudi Arabian peninsula. It was colloquially referred to as “Aden” as it was governed from a large town of that name situated in and around an extinct volcano on the edge the Gulf of Aden. The WAP was, and as the Yemen still is, a country of desert, sand and mountains, very hot and arid with very little flora; no trees, no grass, only scrubby bushes. There are, however, small pockets of agriculture in this seemingly inhospitable land, but these are close to wadi’s (rivers that dry up in the hot season) where most of the crops are grown for export, such as bananas, tobacco, etc. Apart from the British Forces situated mainly in the Aden colony, the population was predominately Arabs and Somalis, most of who were, and probably still are, poor and illiterate. In 1962 I was serving with the Army Air Corps at 653 Light Aircraft Squadron’s “Falaise” airfield, sited about 5 miles inland from the northern side of Aden harbour at a place called Little Aden. At that time the squadron was equipped with Blackburn Bombardier powered Auster 9’s. Each pilot regularly spent a week every month using them to support the Federal Regular Army (FRA) to prevent border incursions by Yemeni soldiers at an ‘up-country’ station called Beihan. About six months after I had joined the squadron we started experiencing abnormal discharge of oil out of the engine breather pipe of our Auster 9’s. Later the source of the problem was found to be premature engine wear caused by sand ingestion. The subject of this first incident is the last trip I did in an Auster 9 in Aden. I had just completed the first sortie of the day at Beihan, which had taken an hour and ten minutes. Minutes after landing the boss of the FRA, Brigadier Lunt, asked me to take him to an airstrip called Ain. On starting the engine all seemed well, but after no more than a minute the oil pressure smartly returned to zero and I quickly shut down the engine before any damage was sustained. The dipstick revealed the oil tank was empty and it became obvious all 14 pints of engine oil had gulped out the breather pipe during the previous flight. Naturally I had to disappoint Brig. Lunt and instead of a ten-minute flight he spent some uncomfortable hours getting to Ain by road. The detachment at Beihan included two R.E.M.E. technicians who tried valiantly to diagnose the problem and revive it. Following their ministrations I did an air test, circumspectly carried out over the long runway, but the oil pressure dropped steadily to well below its normal operating limit as engine RPM was reduced and the engine stopped on short ‘finals’. The technicians tried once again, but the second air test was as much a failure as the first. As an engine change would involve transporting a lot of equipment and more men to Beihan - equipment and technicians needed at our base - it was decided to ‘casevac’ this Auster 9 to the Maintenance Unit (M.U.) at R.A.F. station at Khormaksar just outside Aden. The move was achieved by removing its wings and loading them and its fuselage into a R.A.F. Beverley transport plane. This enabled a detailed investigation of the ‘sick’ engine to take place where special equipment was at hand, while, in parallel, a new one and the wings were refitted. Some weeks later the M.U phoned asking for a pilot to go to Khormaksar to do an air test. We were on the point of leaving when another phone call from the M.U. informed us an R.A.F. Hawker Hunter had accidentally taxied into our Auster! So back into the M.U. it went. By the end of its second repair one of the early Bristol Belvedere helicopters had arrived in Aden on ‘hot and high’ trials. Apparently some bright spark with lateral thinking ability in the Belvedere team heard about our Auster and came up with a brilliant idea. Why not remove the wings (again!) and transport its fuselage to Falaise slung on the hook beneath the Belvedere? Not only would this solve its delivery but also provide a useful hot weather task for the Belvedere, “killing two birds with one stone” so to speak. At that time the only helicopter in Aden was a Bristol Sycamore used for Air/Sea rescue duties, so the noise of one low over “Falaise” drew almost all of 653 squadron personnel out on the airfield to watch the proceedings. The pilot of the Belvedere made one approach to familiarise himself with the ‘field’. On the second approach the Belvedere hovered in front of the audience before starting to descend. I do recall some wag in the crowd said, “What’s the betting they drop it?” When the Auster fuselage was approximately fifteen feet above the runway, descent stopped and, to the consternation of all, it was released. On hitting the ground its tail plane flapped dramatically down ending with the tips almost touching the ground. Conversely, the undercarriage was forced rapidly upwards to a position never included in the design specification; even a trainee Army Air Corps pilot misjudging a short landing would not cause such damage! And one can only imagine the shock loading effect to the brand new engine! At that time I believe an Air Loadmaster positioned himself at the window halfway down the pencil shaped Belvedere fuselage, where he gave descent, touch down point and hook release instructions to the pilot. The story goes, and I cannot vouch for its veracity, that at around fifteen feet the Air Loadmaster coughed. The pilot thought he heard the command ‘Drop’, went into the hover and released the hook! Needless to say our Auster went back to the M.U. for the third time, and I never saw it again for by then I was flying the Immortal Beaver. |

|

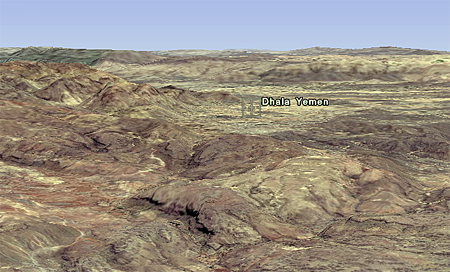

Chapter 2. A Beaver at last! The demise of the Auster 9 in Before I go on to the flying, it is, perhaps, relevant to describe the version of Beaver used by the British Army. It was different in a number of respects to that of a civilian one. First of all, it was the wheeled, landplane model, although there was one occasion when I would have welcomed some ‘floats’, but more of that later. And it had only a two bladed propeller, which these days must be rare. It also had four bomb racks, two on each wing fitted just beyond the wing strut and each capable of taking a 250 lb load, though we never used them for dropping bombs. On the contrary, instead of being employed to destroy we used them to drop supplies to anyone in need of support in difficult terrain, often up blind valleys in remote mountains that the R.A.F. could not easily reach. The method used was to firmly strap the supplies into a pack where the weight was evenly distributed. A suitably sized parachute was then attached to the top of the pack with a line from the top of the canopy tied to the bomb rack. When the pack was released this line would pay out until taut, then pull out and deploy the parachute, and having served its purpose, snap off. This ensured the ‘chute opened more rapidly than would be the case were it allowed to float down freely and it allowed loads to be dropped from only 400 feet up. We all know the nearer you are to the goal the easier it is to score and being that much lower meant assessment of obstacles, surface wind, crosswind and release point was a lot easier. This greatly improved the odds of our reaching the target, which could be only a small clearing. Three ways of releasing the loads were provided, two electrically and a manual emergency handle. One electric method consisted of four selector switches on the lower console in the cockpit, one for each rack. Any combination of these could be selected followed by the pressing the Release button on the yoke. The other by-passed the selector switches and on pressing the Release button all four loads dropped simultaneously. The manual release consisted of two wires, one threaded through each wing and attached to the two racks on that wing. At the other end the wire terminated as a handle in the cockpit at the wing root. Each of these handles could be reached and pulled by the pilot in an emergency. Wing tip tanks were also a feature of our Beavers, but that may be common to many others, possibly even part of the original design. There is a story about those I shall be relating later. The interior of British Army Beavers was not luxurious; in fact for some passengers it was almost Spartan. A pilot and five passengers were catered for in three rows of two seats. However, this configuration could be changed within minutes to one of pilot, two stretcher cases and two passengers, and I had reason to do this on one occasion. The pilot and co-pilot’s seats were substantial, comfortable and came up to the shoulders. They were of the ‘bucket’ seat type, enabling removal of the seat cushion to make room for a dinghy pack, and like all military aircraft they featured a four point full harness. Each seat in the second row was individually made of tubular aluminium with canvas seats and cushions. The third row was made of the same materials, but in a bench seat pattern without cushions and they were not that comfortable. Only a lap strap was provided in the second and third row seats. I imagine the flying and engine controls in our Beavers were fundamentally the same as in all others. However, having seen reports that various engine configurations have been tried and used in Beavers, perhaps I should mention ours were powered by the Pratt and Whitney Wasp Junior; a 9 cylinder normally aspirated radial engine of some 450 H.P., and fitted with a supercharger. The excess power available from this unit was a great help when operating in the hot and high conditions of Interestingly, when the Beaver was undergoing evaluation by the Army there was a proposal to power our Beavers with the Bristol Leonides engine. This was an attempt to reduce costs by “buying British”, and although the Leonides developed 550 H.P., it was not selected. Instrumentation was the standard ‘blind flying’ panel supplemented by Radio Compass (NDB) and ILS, though there was no ILS in In addition to the normal V.H.F. Air Traffic radio we also carried another V.H.F. radio to communicate with our forces on the ground when on manoeuvres or operations. Now to learning to fly it! I freely confess to not being that impressed by my first sight of a Beaver. Once flown, though, you couldn’t fail to admire it and I soon became a great fan and told everyone “it’s great to fly”! And it was, and I warrant, still is. With its robust airframe, powerful engine, large responsive flying controls, plenty of flap, great S.T.O.L. performance and high serviceability, it became my firm favourite. And I wasn’t the only one; all Army Air Corps (A.A.C.) pilots who flew one loved it. Its fame was such that both fixed wing and helicopter pilots who had not flown it were envious of those who had and they, too, wanted to get their hands on one! By this time I already had about 300 hours in my logbook, so my conversion to the Beaver did not take too long. Of course, in addition to learning to take off and land there were EFATO’s (Engine Failure After Take Off), gliding, forced landings and short landings to master. As an aside I always remember the saying given by one of my early instructors “Just remember: take-offs are optional, landings are mandatory”. Other skills that had to be learnt were the use of the variable pitch propeller, manifold boost pressure and managing the five fuel tanks. But after about fifteen hours it all seemed to gel together, culminating in release for me to take passengers. After a few more hours doing the “rounds” of all the commonly used airstrips the Beaver became second nature to fly. But as the saying goes, “familiarity breeds contempt”, so I mentally disciplined myself to retain concentration, not become over confident or adopt slapdash attitudes; bad habits to be avoided at all costs. One of the regular, almost daily flights we made was to an outlying area called Dhala some 55 miles due North of Aden. To get there we first had clear the approach lane to Khormaksar’s runway 09 by less than 400 feet. Khormaksar, if you remember, is the R.A.F’s We could go high, abiding by the Quadrantal Flight Level rules. Because Dhala was 4500 feet above mean sea level (A.M.S.L.) and weather was rarely a problem, Flight Level 50 was the one most often used. This was usually adopted if there were any passengers on board, particularly if they were wearing peak caps decorated with scrambled egg (high ranking officers). A smooth but uneventful flight. But having left low level we often stayed low. It was more interesting, especially if alone, though some passengers found it quite exhilarating. It enabled us to practice our low flying skills and it kept us away from any R.A.F. aircraft going the same way. The terrain up to Dhala changes in two stages and does so roughly at the halfway point. The gradually rising ground of the first half is covered almost entirely by sand; rocks being rare and later. At the next stage it is now mainly rocks interspersed with sand. Then more and bigger rocks climbing higher and higher until they become mountains. All the way it is dry, except where wadis (dry river beds) have cut temporary watercourses through mountains and desert during the ‘Hot Season’ from the thunderstorms that drench the highest mountains. The only connecting feature between these two areas is a wadi that runs roughly due North / South down through the mountains South of Dhala. During its existence the wadi has cut a wide, deep channel through the rocks and sand. The water from it drains across the desert, irrigating the banana plantation at Lahej on the way, but then, like a large spread hand, the water sinks down into the desert through its “fingers” about 5 miles before the outskirts of the Aden Colony. However, It is this wadi that provides light-hearted relief to us pilots who have done this journey so many times before. Flying North just above the ground there is little sign of the wadi until a few miles South of Lahej. Then, as the ground rises quite quickly, the wadi becomes deep and wide; some 50 feet deep and 100 metres wide. Yes, it’s big enough for us to fly down without being seen because there is little water flowing down it. But before doing so we check the road that runs parallel with the wadi all the way to the mountains for signs of traffic coming from the North. The telltale signs can be seen miles away; the spiral of disturbed sand curling into the air from the knobbly tyres of a vehicle. That is our target. Down into the wadi we go. We don’t need to gauge his distance: in these wide-open spaces that spiral of dust can be seen getting closer all the time. When he is about half a mile away, up over the rim of the wadi we fly and straight down the track. The wheels are only a couple of feet above the ground as we speed towards the Arab lorry at 100 knots. I remember the saying “Wait till you see the whites of their eyes”, but discretion takes over and at 50 metres I pull back on the yoke and we are over with plenty to spare. Next episode: landing at Dhala. |

|

|

Chapter 3. Downwind for Dhala Having shown the Arabs how to drive a Beaver down the Dhala / Dhala is in a dry, dusty, undulating bowl some 5 miles wide and 10 long, with the The airstrip at Dhala is a dirt surface some 800 metres long cut out of a ridge facing Jebel Jihaf, a mountain. It is completely open, but a few potholes, the odd twig and the occasional can punctuate the runway. It is surrounded by dry bushes, sand and rock, and dominated by the Jebel. Half a mile to the southern side of the ‘strip’ is the The first 200 yards of the ‘strip’ are level, but the remaining 800 rises at about 1 in 10 in the direction of Jebel Jihaf. When I did my first landing at Dhala I was accompanied by a pilot who knew the airstrip. His advice had been threefold: “One: always land uphill towards the jebel”. “Two: on your approach do NOT lower landing flap until lower than 200 feet above the runway. Above that height you can do a ‘go-around’, below it you are committed to land, because the ground rises faster than you can!” “Three: takeoff downhill, irrespective of the wind direction”. Excuse me, what was that? I’m committed to land once below 200 feet? So what happens if a red kite hits the aircraft; what if something stupid is done on the ground! And that mountain; an intimidating sight at any time, which I don’t want to tangle with. However, most landings at Dhala are incident free, but at the back of my mind I recalled something about rules and exceptions. My first incident at Dhala had little to do with flying. The approach and landing were quite satisfactory. I taxied up to the parking area at the top end and to one side of the runway, did the run down checks and stopped the engine. As I jumped down I noticed there were a quite a number of tribesmen standing around. But one of them was different to the others. It wasn’t his dirty loincloth covering only the barest parts of a dust covered, dark skinned body or his badly worn sandals, nor the absence of the curved bladed knife common to most tribesmen. No, unlike any of the others, he had a metal ball of some eight inches in diameter attached to his foot by a steel anklet and a very short chain. I was shocked and, for some seconds, speechless. Yes, I knew that up-country Arabs lived an almost medieval existence, but I was appalled by this confrontation with feudal life. From an early age I had learnt from books, films and plays the ball and chain was either a tool of punishment and torture, or the exact opposite where in situation comedies the incumbent picks up the ball and walks away, or it is not a ball but a balloon. Right now my mind was firmly rooted on punishment, so I asked why we, the British, condoned such practices. I was told it was not punishment. Apparently this Arab was mentally retarded and as it was the family’s responsibility to look after him, the Emir had decreed the ball and chain to be fitted to prevent him from wandering away from his ‘home’, thus my assumption about punishment was wrong. This is the “up-country” way of dealing with a social problem: it is Arab logic. Make the chain very short then it cannot be picked up, not even when bending over. It’s very effective; it severely confines the unfortunate owner’s movements. To move the ball it had to be dragged, painfully and slowly, and the wearer’s pain caused by the anklet rubbing the flesh bare at almost every step is conveniently ignored. It is barbaric and unkind, but it’s cheap and it works, and the Emir keeps control without spending a penny. I had done many landings at Dhala when the next incident occurred. It was late afternoon, still very hot and dry, and I was getting tired after starting very early that morning. I was returning three FRA officers to their battalion and was to pick up two other passengers for Khormaksar, the R.A.F. base at Oh, my God, now what? Will the pesky thing get off, or be chased off, before I touchdown? Come on you idle animal, move! And why aren’t those FRA soldiers chasing it away? These thoughts took but seconds and so did the loss of spare altitude. No, I’ve got to overshoot before it’s too late. Throttle open; get a bit of spare speed and then a tight left turn. Even then we only just missed the rubble of old Arab hovels. It was close; too bloody close! Later, back on the ground, a few well-chosen Anglo Saxons words were despatched by me to the Arab N.C.O. in charge of the airstrip party. Although it had to be translated, I could see from his facial features the nub of my wrath had hit home. “Imshi, you Arab twit”! Next time I will be dealing with an incident that was even more frightening – the Radfan |

|

Chapter 4. Rush hour in the Radfan The Radfan is a mountainous area stretching northeast from Dhala up to the We in the Army and R.A.F. are forbidden to over-fly it. To do so invites one of two punishments: being shot down, and if not killed by that, suffer a nasty death at the hands of the tribesmen; or having manage to return to one’s base, face a court martial for disobeying a General Order. Neither is palatable, and any one within a modicum of commonsense complies with the order. Hence when doing the “round robin” trip to other outlying stations we fly round the Radfan, going south from Dhala, then west over the Zinjibar plain before turning northeast to Mukerias, Lodar, Ataq and Beihan. The flying distance on the outbound leg is doubled by this “dog-leg” However, for some time diplomatic efforts have been made to bring the Radfan under British control. After protracted talks the Political officers have been able to gain agreement with the local chieftains to hold a meeting in the Radfan with British senior officials and Service officers. The objective of this gathering is to overcome the existing distrust and strained relations, and prepare the ground for the future entry of the Radfan into the South Arabian Federation. A date is fixed and we are given the name of an airstrip in the Radfan. Identified on the map, it is on an oval bowl shaped plain, some 5300 feet up and surrounded by mountains. We are told that one of our Beavers is to accompany the Prestwick Twin Pioneer that will fly in the “Big Wigs”. Our Beaver will carry the “not so Big Wigs”. A briefing is convened with all the participants a couple of weeks before the event. It covers the overall plan with key events and timings; the political situation, which I gather is still not that good; the flight plan; the agenda for the discussions; arms to be carried, and the contingency plan. We all come away confident everything has been covered. When the day arrives it is an early start. From my flat in A little later both aircraft taxi out and take off and, having cleared the runway, head just east of north for our destination. To match the “Twin Pin’s” speed and to keep open formation with him I must cruise a little faster today. There’s only a light breeze coming from the East so the flight will take only about 40 minutes. Twenty minutes into the flight we hear the radio call of the four-engine Avro Shackleton that is to accompany us and act as command and control for this operation. Ten minutes later we hear the two Hawker Hunter fighters that are coming too. These are to fly “top cover” over our destination as a show of strength and to discourage any treachery and trouble. Soon we are over the plain we marked on our maps. This bowl contains a light brown, cake like mixture of unforgiving sand, rocks and hills, interspersed with small fields of pale green and stunted agriculture. We find the airstrip without difficulty as finding remote landing places is something we do quite regularly. But we don’t know this one; no British aircraft has landed here for years, so we do a couple of circuits to assess the approach, the surface and the under and overshoot areas, and in particular the reception committee. Satisfied all is as well as can be expected we call the “Shack” to notify him we are going to land. And in we go. It’s not a difficult approach and the ‘strip is plenty long enough for a Beaver. The “Twin Pin” does not come in until all appears well on the ground. Prudence dictates I should park close to the runway as up-country tribesmen have a strange way of welcoming visiting dignitaries. Sure enough as my lower ranking passengers deplane there is a fusillade of shots fired vertically into the air by the local Sheikh’s henchmen. This is the traditional method of greeting. The first time it happened to me I made a fool of myself; I instinctively threw myself to the ground. Now it seems relatively harmless, but those bullets have got to come down somewhere. If any one of them bores a hole in my skull I shall be very annoyed and, even if unscathed, I don’t want any hitting vulnerable places on the Beaver. All goes well, however, and after formal introductions where official etiquette is observed there is an exchange of gifts between both parties. The Big Wigs are then conducted to a large, several-storied, mud brick “palace”, painted white with wooden windows decorated in bright colours. We, the “bus drivers”, follow on, for we too have been invited to the palace for dinner. Through a door and up several flights of stairs we go. The riser of each step is small by western standards and the tread is long; it needs two paces to reach the next step, with each one covered in a rush like mat. There are few windows, even less in the inside wall. Eventually we reach a landing that would please a cobbler, for here there are many pairs of discarded shoes. They rank from the simple, worn sandal of the Sheikh’s followers to the polished black and brown of the visiting delegates. This is an Arab custom, shoes are not worn in the house and not when eating. Why? Because you do not sit up to a table, but on the cushioned floor, and dirty shoes are not kind to cushions. Having removed our shoes it is equally important not to point the soles of your feet at anyone, as this, too, offends Arabs. There are no knives, forks or spoons; nor is there a serviette or a menu. And the food we get would have been unacceptable in English restaurants, but it is substantial. There is no starter and no wine, for Arabs do not drink alcohol. Once we are all seated men servants bring in plates and many large platters of hot, curried goat and steaming rice. These are followed by an equal number of small dishes of goat’s eyes and honey, delicacies to the Arabs. When offered one I decline very politely. After the Sheikh has said a Muslim “grace” we take rice and goat from the platters using our right hand. The left hand is not used, because it is considered “unclean” and is for other, more intimate uses. When this meal is finished and the plates cleared away, sweetmeats and black, sweet coffee is served. The food was satisfying, hot and well cooked, but now there seems to be some urgency to get on with the talks. A crowd grows on the landing searching for shoes, and it soon becomes obvious the shoes belonging to an Army colonel have “walked”. The Sheikh is humiliated by this insult to his guest and issues orders in a grindingly annoyed voice to one of his lackeys. Unable to understand Arabic I don’t know what they are, but I can guess. If caught and found guilty when tried by the Sheikh, the sentence will be “Off with the offending hand”. Similarly, the colonel is red faced with annoyance and embarrassment, but reluctantly passes it off in order not to prejudice the talks. I, however, cannot escape the humour in the situation and quickly nip down the stairs before I start laughing. Throughout all this; the welcome, the dinner and the official formality, we have not seen one woman. And nor will we, for in Arab life the women look after the family, the children and the domestic tasks, and certainly do not play any part in politics. They are very much part of an Arab’s private life and are seen only by relatives and friends. They will not be present at, nor take part in any of his business dealings. The Arab male is very much the head of the house and he makes all the decisions, often without consulting his wife. Although most husbands are very kind to their spouses and children, Arab customs and law allow him a great deal of latitude in what he can do, and some of these laws might appear strange and cruel to us. Alan and I go back to the airfield to await the end of the talks. We pass the time with our “Twin Pin” colleagues, exchanging aeronautical stories and anecdotes. The skies above rumble from the “Shack’s” engines and the roar of the Hunter’s jets. I’m sure the Hunters are a new pair, though; for their endurance isn’t long enough to cover the time we have already spent on the ground Strangely, the talks don’t last that long, which isn’t very encouraging. However, the Big Hats seem reasonably happy as they walk back towards us. Then, suddenly, that dreadful sound: “rattat tat, rattat tat”. Once the initial shock of that machine gun fire is over consternation and panic break out, as bullets seem to whine past in all directions. Arabs are dashing for cover. The Big Wigs are racing for the aircraft. Alan turns as he starts running, shouting to our passengers, “Get in the plane”. Instinct takes over: out with the revolver and run like crazy for the plane, firing on the way. “Where are the bastards”, I gasp at Alan, but he doesn’t know, and we’re not stopping to look. Within seconds I had broken my previous best time for that distance, whatever it was. Back at the Beaver we all tumble in. Forget pre-flight checks, just get it started and go. The two of us carry out enough essential actions to get XP773 moving and she’s ready for take off by the time we reach the end of the ‘strip. Almost tipping it on one wing Alan turns her into wind, opens the throttle and away we go. The “Twin Pin” has narrowly missed beating us, but is also airborne with great haste. Her captain tells the “Shack” the firing appeared to be coming from the opposite side of the airstrip to the Sheikh’s palace. Once the “Twin Pin” and Alan have called “Airborne and clear of the ‘strip the Shackleton flies overhead directing the strafing Hunters to the targets that had been identified. When finished the “Shack” bombs the same areas and the runway. We, of course, were on our way back to base while this was happening. We are shaken and disturbed by the perfidy of the Arabs, but keep ourselves under control. Nearer to “home” we start to relax, but on arrival find two bullet holes in XP773. This and the premature relaxation set off a nervous reaction making my hands tremble. One of the bullets entered the side of the engine cowling and deflected by it had gone through some of the cooling fins at the top of the engine, finally going through the top of the cowling. Thank the Lord it had not pierced a cylinder or piston. The second bullet went straight through the fin, making a neat entry hole, but a jagged exit. None of our visitors was wounded, but the odd scratch was caused by diving for cover and falling over in our haste to be gone. Later our “Twin Pin” colleagues phone to say no one in their party suffered any serious damage, and kindly enquire about our welfare. I think the Radfan leaders were keen and confident of eventually concluding a deal with the British and their men were under strict orders to behave. I suspect the uprising had been the idea of the ill disciplined insurgents from over the That was the first and only time I went into the Radfan, and not surprisingly the order not to fly over the Radfan remained in force. |

|

Chapter 5. Murder, Motoring and Meteorology at Mukerias Today, The African Rift Valley cuts a deep gash through eastern

Three miles ahead I can see the dramatic, near vertical, solid rock rising around 3000 feet from the Lodar plain, a wall of rock starting 5 miles to the west and running east for roughly 12 miles. Here its flat top gradually changes to jagged, saw tooth rocks which eventually subside into the desert some 30 miles northeast. We pilots in 653 Squadron colloquially refer to this towering formation as “the escarpment”.

On top of the escarpment is Mukerias. An unimportant, insignificant, scruffy little village. The sort you normally wouldn’t give it a second look. But it is important. It sits astride one of only three ‘main roads’ leading from Sanaa, the capital of the Unlike Dhala, Ataq and Beihan, each of which are occupied by a battalion of F.R.A. soldiers, Mukerias is garrisoned by a Company of 120 men from an English infantry regiment. The fortified encampment they occupy is only four miles from the This position was chosen because it is the last defensive opportunity before the road disappears over the edge of the escarpment down the 3000 feet to Lodar and on to One is the drive down. Although dropping down the 3000 feet to the Lodar plain takes only three miles, it entails negotiating 59 steep, hairpin bends down a rough, rutted track. This journey should only be tackled by experienced drivers driving slowly and carefully in well-maintained vehicles. Over the years there have been many accidents, most of which were attributable to brake and clutch failure or a minor lapses in concentration. Invariably the vehicle toppled over the edge, somersaulted down the steep sides, smashed violently into the jutting, jagged rocks, reducing it to matchwood. Sadly, the occupants of these accidents rarely survived. Those that did were so severely injured it ended their army career. During tenure of this outpost a number of British servicemen have died this way. Clearly it would be folly for inexperienced The second danger is even worse. It would combine the risks of the first while providing the R.A.F. with the golden opportunity of strafing those lorries slowly descending that steep road. Imagine the destruction and loss of life to the Enough of history and tactics, now back to Mukerias. The airstrip there is far from ideal. It is not even as good as the one at Dhala. Over the years the treadmill of aircraft wheels has eroded large oval sandy depressions down the ‘strip’. Heavy thunderstorms have then stirred the earth and sand into glutinous mud, to be packed hard into a concrete like surface by the burning sun. Though it is over a thousand yards long, it is the ‘strip’ I like the least. Its popularity is further diminished because it is hot and high. At 6600 feet above sea level, there is a bigger Density Altitude problem here than any other airstrip. During the hot season the early afternoon temperature often reaches between 30°C and 35°C. This exceeds the ICAO Standard Atmosphere Law for this height by 28 to 33 degrees. Since the ICAO Law is what all aircraft engines, systems and instruments are designed and calibrated against, there is a significant adverse effect caused by this ‘hot and high’ deviation. Luckily there is a very simple rule that can be applied showing its effect. Take the difference between the number of degrees actual and that of ICAO (say, 31) and multiply it by the arbitrary figure 120. Add that to the physical height of the airstrip and you have the Density Altitude. In this instance it is the same as asking the aircraft engine to power the aircraft as though it is at 10, 300 feet. Of course, all navigation confusers (hmm, sorry, computers) will give a similar answer, but in case we lost that, we had also been also taught to do all calculations mentally with only a map and pencil. Confronted with a Density Altitude situation I ask myself a number of questions: What is the All Up Weight (AUW) of the aircraft with fuel, passengers, etc? At this AUW and in these conditions what length runway is needed to get airborne? Is the airstrip (plus a contingency factor) at least as long as this? If the answer is “No”, do I offload some weight or wait till late p.m. when the temp drops and performance is better? Has a thunderstorm has just passed? If so it may be cooler. Conversely the runway may be inches deep in water, which retards acceleration. Shall I mark a point on the runway by which I must be airborne or take off be aborted? I’m lucky; I have previous experience of Mukerias. There was one occasion, when having satisfied the above questions, it still took an Auster 9 around 700 yards to become airborne. I was on the point of aborting the take off when we lifted off the ground. And the rate of climb was appalling, no more than 150 feet a minute. I can remember thinking at the time, “it normally takes only 200 yards at sea level to unstick”. Not that it helped. And a memory trigger always pushes these considerations to the forefront of my mind on all subsequent visits to Mukerias. One other incident about the weather at Mukerias comes to mind. On this particular day I had been on the ground for about half an hour when a heavy thunderstorm started, a not uncommon occurrence up-country during the “hot” season. The usual sequence of events: a few crisp gusts of wind as the black, low, mamma cloud gradually approached; lightning and thunder, distant at first, but getting brighter and louder; a smattering of heavy rain drops. Then Thor arrived: quick, strong gusts of wind; torrential, penny sized drops of rain and hail; lightning, bright as a momentary, magnesium flare combined with ear splitting, whip cracking thunder. After making sure even the dead knew of his visit he left about half an hour later. In his wake everything was sopping wet; muddy pools and streams everywhere. The ‘strip’ was almost awash with puddles of every size and shape. On the plus side there was a slight drop in the temperature, and you could almost hear the parched plants sucking up the muddy water. Some fifteen minutes later I heard and saw a Vickers Valetta, an R.A.F. twin-engine transport coming into land. On touching down it was immediately in the rainwater. It reminded me of the roller coaster rides entering the pool of water at the bottom of the steep rail. All one could see were two enormous fountains of water arching either side of the cockpit. This continued down the runway, but not far, as the braking effect of the water brought the Valetta to a rapid halt. Having gingerly taxied into the parking area, the captain made an inspection of the aircraft. There he found the flaps were no longer flat and retractable. On the contrary, as befits the effects of water they were best described as “scalloped and wave shaped”. It left about an hour later for Khormaksar, flying back all the way with half flap down. It pays to be careful; no two flights to the same place are identical. Let us now return to the operation at Husn Suffa. By the time I arrive at Mukerias the F.R.A. have hacked a landing strip out of the bottom of the valley by removing the low growing plants. I supervise the loading of the aircraft before taking off and obtain the map reference of the ‘strip’. It is reputed to be around 500 yards long, but I’m warned the surface is loose, uneven, soft sand. I conclude it will be all right getting in, as long as, once down, I keep the yoke well back. But getting out is likely to be an altogether different “kettle of fish”; I’m a little concerned about that. On arriving overhead I have a good look around. It’s far from ideal; the valley is narrow; its “walls” are only about 500 yards across, so I cannot fly a normal circuit. However, the under and overshoot are clear, no trees or obstacles. First then, I must work out my approach. I decide to fly a long “downwind” leg, and dispensing with a “base leg” I do a continuous turn on to “finals”. I get nicely settled on the approach and surprise myself by making a good landing. To prevent that soft sand from tipping the Beaver on its nose I wrap and lock my left arm around the yoke. It does the trick, but now I can feel the rapid deceleration as the wheels sink into that sand. Surprise again; this time at how short the landing run is. Having stopped, a lot of power is needed to get “her” moving again, and turning is laborious. Once parked at the take off end of the ‘strip’ a group of F.R.A. soldiers quickly unload the gear. In its place they stack empty ammunition and ‘compo’ (food) boxes, and a broken tent. An officer tells me he has already signalled ahead to Mukerias for more stores, but can I also bring more paraffin (kerosene) for the cookers. Oh yes, and some tea, sugar and milk for the ‘Brits’ in the group. On enquiring how the operation is progressing I’m told “It’s difficult because both tribes are shooting at us as well as themselves. They don’t want us interfering in their own affairs, but we’ve got to separate them”. I start up, do the checks and prepare for take off. I’m still concerned about that soft sand. Wait, I remember someone saying that to keep drag down to the absolute minimum and reach “rotate” speed as quickly as possible they didn’t put down ”take off flap” until the I fully open the throttle against the brakes before releasing them. For a few seconds nothing happens, but then the wheels rise over the troughs made by them and we are moving. At first the gain in speed is slow, but as acceleration increases and lift is generated over the wings the weight is reduced and then the speed increases rapidly. At 40 knots I pump the flap lever to “take off flap” and the Beaver leaps into the air. I establish the normal climb attitude and speed and out of the valley we climb. It crosses my mind I was well down the ‘strip’ before becoming airborne. I wonder if the technique of delaying flap gave any benefit, or was it cancelled out by my response time between registering take off speed and putting down flap. I make a mental note to put some markers down the ‘strip’ before the next outbound trip. This sequence of events continues almost unchanged for the next few days. Only the freight alters. Sometimes I take in items I consider unusual for an operation: kippers for the officer’s breakfast, sandals for the Arab soldiers - presumably lost while patrolling at night, and a few cans of beer for the British warrant officer. One day I take Brigadier Lunt, boss of the F.R.A., for a visit. Most days, though, it is food, water and blankets – oh, yes, it’s dammed cold at night at 7000 to 8000 feet, even at these latitudes. On the return flights most of the cabin is filled with the “empties”, but on two occasions I take a wounded soldier, though these are not serious casualties. On the second day I put out some markers along the runway and compared a normal take off against the delayed flap operation. The results were inconclusive in terms of take off distance, but the late use of flap gives a very positive “unstick”. By the fourth day the F.R.A. have separated the protagonists and confirmed the cause of the feud; the murder of one man by another from a nearby tribe. Talks to settle the dispute were prolonged because the wife of the dead man could not be consulted. For Arab custom decrees it must be the male next in line who becomes head of the family, in this case his 14-year-old son. He was offered a fairly substantial sum of money to call off the fight, but this, too, would not suit Arab pride. “No”, said the son, ”Only if you execute the murderer will I call off the feud”. After protracted talks and much pressure by the F.R.A., the other tribe agreed to the sentence. However, this posed another difficult problem for the F.R.A., for it is cowardly for an Arab to shoot another without reason. Fortunately, one of the F.R.A. soldiers was a member of the murdered man’s tribe, and he was volunteered to execute the offender. Neither of the tribes will be told who the executioner is, to avoid any future trouble, and only those in the F.R.A. with a “need to know” are privy to this. The sentence is to be carried out today, after which both tribes should settle down to normal life. This incident will rankle between these two tribes for some time, but they have given their word to keep the peace. Only time will tell. I spend the next two days back and forth to Mukerias, transporting as much equipment by air as I can, to save it being trucked up the valley. My job is over, but it has put more experience under my belt, both about flying and the Arab culture. Next time: tip tanks and a casualty at Ataq. |

|

Chapter 6. Trouble with Tip Tanks, and a casualty at Ataq. It’s I nip outside to inform the N.C.O. in charge of the servicing crew, Corporal Hackett, to fill them up. Meanwhile I sign the Authorisation book, the document in which my Flight Commander has entered details of the flight and his approval of me to carry it out. I change into my flying suit, gather up my map and navigation kit and walk out of the hangar. Two petrol tankers are parked across the hangar door and in front of XP774, one hitched to the other. Momentarily a “Why” flashes through my brain, but goes instantly: I’m already late, and the priority is to get going. The corporal, a member of the Royal Electrical and Mechanical Engineers (R.E.M.E.), is refuelling the port tip tank with the filler neck. Just as I put my things in the cockpit he gets down, comes over to me and in a downcast voice says, ”Sorry Sarge, something’s gone wrong; somehow we’ve filled the tip tanks with kerosene, not avgas”. My face goes from calm to angry surprise, “What? Then to annoyance, “How the hell did that happen”. Then to suspicion, “And why have we got two bowsers linked together? Has that got anything to do with it?” “I don’t know, sarge, but it might. The tankers are linked together because the engine on one of them doesn’t work, whereas the other does. We should be able to use the good one to pump the avgas out of the other, but it doesn’t seem to have worked. It looks as though it’s pumped its own kerosene instead”. Exasperated I reply, “Looks like it? I’d bet on it”. In a slightly calmer voice I ask,” How did you find out?” “Well, when I took the filler neck out of the tank it was wet, and avgas dries instantly. So I smelt the neck and it was kerosene, not avgas”. “Well done”, I said, my irritation changing to relief. What was it that had provoked this man to question something many others would have missed? Was it instinct? Common sense? Good training? Experience? Curiosity? …… Who knows, probably a combination of some or maybe all of those attributes. Whatever it was, it saved my life, for just imagine what could have happened had he not noticed. I start to think about that as I return to the crew room to phone my passengers at Khormaksar that the flight will be late. I go through the routine in my mind. Start the engine on one of the three belly tanks: the tip tanks can’t be selected for that; they are just containers, and all you can do with them is transfer the fuel by gravity to one of the belly tanks, and they’re all full right now. Thus there is no check you can perform on the tip tanks before take-off, save the one the corporal did. So, off I would have gone, oblivious to the lurking problem. After flying for an hour I would check the fuel gauges to see if I could transfer some of the avgas to the belly tanks. Ideally I want the tip tanks empty before landing to avoid putting any strain on the wings. Good, the centre belly tank is down to about 6 gallons, so I switch to the rear belly tank and start transferring fuel from the tip tanks. All is fine, until later I switch back to the centre belly tank – unbeknown to me, now almost full of kerosene – and then things start going wrong. Within a short time the engine begins to complain: it doesn’t like this fuel, its octane rating is far too low, and it’s oily, so the spark plugs foul up. The fuel pump and carburettor start to clog up too. Within seconds the engine starts to run rough and there is a marked loss of power. It’s time to find somewhere to land before the engine stops. It’s also time for a Mayday call. But no, once more God was watching over me, he and the corporal saved from that. Alan, my Flight Commander arrives and seeing XP774 and the bowsers on the apron, asks “What the Dickens is going on? Why haven’t you gone?” I briefly explain what has happened, strongly emphasising the corporal’s part in the events. “Whatever the outcome of any inquiry, Sir, Corporal Hackett’s exceptional attention to detail at such an early hour in the morning ……his sixth sense …… whatever, saved my bacon. If he is charged, I would like to act as a witness in his defence”. “Yes, sergeant, all right, calm down, I’ll take over now”, says Alan acknowledging my strong feelings on the matter. “And give staff sergeant Tilley my compliments. Tell him to have XP775 rolled out and ready in five minutes … with the tip tanks full of avgas”. And almost as an afterthought, “Change ‘XP774’ to ‘XP775’ in the Flight Authorisation book and I want you off the ground in six minutes!” Corporal Hackett was charged, but received only a ‘reprimand’ for the bowser mistake. On the plus side he was commended for his intuition, perception and instant diagnosis. That act was publicised in the Army Air Corps quarterly magazine as an example of the standard to which all R.E.M.E. aircraft technicians should desire to attain. The days that followed passed uneventfully, until a trip to Ataq. I’ve been to Ataq many times. It is a small, but relatively tidy village by Arab standards, dominated by the usual big, white, several-storied house belonging to the local headman. I don’t think he is an Emir or a Sheikh; I’m sure I would have heard by now. He certainly isn’t a Sultan. How the locals survive here, I do not know. The village sits in a plain of sand on which nothing grows. To the north, nothing but sand as far as the eye could see. To the east, west and south there are mountains, but they are miles away. And what can they get from them? Water, perhaps, but nothing else as far as I can see. The flight I am to do today is simple: pick up three passengers at Khormaksar, take them to Ataq, and then wait until they are ready to return. No tip tanks. No weight problems. Should be a doddle. We land at Ataq just after an Aden Airways Dakota (DC3) leaves - they are a subsidiary of B.O.A.C. Garrison activity here is pretty laid back. Nothing of note has happened here for a long time, so only high-powered visitors are met, and I don’t think my passengers fit that category. So it comes as a bit of a surprise, today, when we are met by one of the British officers of the F.R.A. One of my passengers must be more important than I thought, and the Major is the welcoming party. No, I’m wrong, it’s me he wants to speak to. Apparently there was an incident on one of the ‘roads’ last night. A mine exploded beneath a Land Rover while on a recce and the driver is badly injured. “Can you get a stretcher in there?” he says, pointing at the cabin full of seats. And in his concerned voice “Can you take him to Khormaksar?” And then, “Oh, and a medical orderly as well?” “Yes, Major, just give me a few minutes and I’ll be ready”. I catch up with my passengers who are already walking to the camp. “Excuse me, Sir, I’ve got to casevac a chap to Khormaksar who’s in a bad way, so I’ll have to leave you here. I’ll try to get back today, but if not I’ll make sure my Flight Commander knows you need a flight tomorrow”. I could see they were not pleased, but they said nothing, for they knew the injured soldier’s need was far greater than theirs. In their facial expressions I could just detect, “There, but for the Grace of God, go I”. From behind the rear seats of the Beaver I retrieve some webbing straps and with them change the seating layout into two stretcher cases and one seat, stowing the rest out of the way. I deliberately leave the straps loose; it makes it easier to slip them over the stretcher handles. Within minutes the patient is carefully carried out on a stretcher. It is impossible to ignore the pitiful state of the poor devil. His left leg is a mass of bandages over which there are large blotches of bright, red blood. The back of his neck and head is pitted with red nicks, bruises and plasters. A torn shirt reveals his left arm and the left side of his back are swathed in bandages too. The medics lay him flat and strap him to the stretcher, and it’s obvious he is in pain. I explain to the bearers how the stretcher must be manipulated to get it in the cabin and the straps. To ensure the minimum of discomfort to our unfortunate comrade six men are needed. The four holding the stretcher wait for the other two to climb in the cabin. They then take the handles from one end of the stretcher and move a bit further down the cabin. Those outside who have just let go, climb into the cabin. The two outside extend their arms above their heads and lift the stretcher as high as possible for the pair inside to reach the handles. Released of the weight, the last pair climb in and feed the strap loops over the four handles. Then I make sure all is tight and the patient is as comfortable as is possible. The medic accompanying our patient checks he has everything he needs for the patient and climbs into the seat next to the stretcher. As I get into the pilot’s seat I ask the Major to signal the British Military Hospital (B.M.H.) at Steamer Point in

From then all went well, the wounded soldier was taken off the Beaver straight into an ambulance and to hospital. I was lucky, too. I didn’t have to go back to Ataq: as soon as the signal arrived at Falaise, one of my colleagues was detailed to leave immediately for Ataq. I’m just a little surprised we didn’t pass one another en-route! One good thing came out of this, though. We pilots in 653 are now not allowed to land at any ‘strip’ until a vehicle has driven the full length of the runway to check for mines. I’m happy with that, but I don’t think the Landrover drivers are! Ah well, all in a day’s work! Next chapter: Beihan |

|

Chapter 7. Border bother, blatant lies, a burden, burning sun, and bullion and bullets at Beihan. I spent two years in ‘ I have been in ‘ This prompted Brigadier Lunt, commander of the F.R.A., to order a battalion to Beihan to build an encampment close to the airstrip in the valley of wadi Beihan. Although not finished yet, they are now well entrenched with a smooth operating garrison. Within three weeks of Lunt’s decision we in 15 Liaision Flight of 653 Squadron were there too, performing reconnaissance (recce), liaison and supply tasks for the F.R.A. using Auster 9’s, see Chapter 1. The arrangement is that each pilot, in turn, spends a week on this detachment, and to ensure aircraft hours and servicing are maintained at a consistent level they, too, are to be rotated. However, use of the Auster 9 was halted some days ago following a series of serious oil loss problems, resulting in engine changes at ridiculously low hours. In the weeks to come the cause of this fault will be found to be premature engine wear caused by sand ingestion. Now we only use Beavers; a decision welcomed by all pilots in 15 Flight, particularly me, as I was the first to encounter the oil-gulping problem, and a very thought-provoking incident it was, too. For some time those in command in The first is that These factors are worrying to the British government and to Middle East Command in To those of us who spend most days “up-country” there are obvious signs of change. Ten days ago I went to Dhala and was surprised by the number of tribesmen congregating near the airstrip. Many of them are different to the local inhabitants. Their deep-lined, very dark-brown faces are hard; eyes are set into deep sockets; noses curved and sharp edged like scimitars. They look rough and tough and carry Arab “baggage”. But, above all, they are well armed: all of them carry the traditional, highly decorated, curved knife and the ‘jezail’, an ancient, long barrelled, embossed rifle with a curved butt. About twenty minutes after I arrived a Beverley landed. It’s a large, four-engine, transport, which looks a trifle like a whale with wings and a forked tail. To land one is like rolling a block of flats on to the runway. It disgorged some equipment and a few passengers, but little compared to its total capacity. Then, to my utter surprise, the Beverley’s Loadmaster signalled the hard-faced tribesmen to climb aboard. “What the devil is going on here?” I muttered to myself. An R.A.F. officer standing nearby must have heard me, for he answered, “They’re Royalist tribesmen going to Beihan. Once there they can, if they wish, cross the border to where their Royalists friends have a much stronger grip on the land”. All of this is said tongue in cheek. My intuition tells me I should cast a Nelsonion eye at it. Being busy talking to the R.A.F. officer I didn’t count how many of them boarded, but from what I did see I guessed it to be over the normal amount. As most Arab men don’t weigh as much as us, I doubt the A.U.W. was exceeded. Anyway, I can’t imagine the captain allowing that to happen: were anything to go wrong while carrying out this covert operation, large dollops of a smelly, brown mixture would impact on a fast spinning fan. By chance the following day I went to Beihan and witnessed a Beverley unloading its cargo. There are no prizes for guessing what it was, but it was not carried off; it walked. My wife, Susan, and I have a flat in Maalla; that part of Aghast at such a blatant lie I said to my wife, “But I saw this happen only a few days ago. How can he have the audacity to refute it?” But he did. It’s called political expediency. It’s Monday, and my turn to go to Beihan for a week on detachment for the F.R.A. I fly XP775 up there and as usual when flying in “ On arrival I get a quick briefing on the current situation from David Ashley, the chap I’m relieving. Then he makes an enthusiastic departure in his Beaver, obviously looking forward to a slightly more civilised period in I report to the F.R.A. Quartermaster, an English major. He greets me with the news, “I want you to take some kit to Ain (or Ayn); they’re short of one or two things”. He and I have met before and I know what he really means: he’s got a pile of equipment waiting for me. “Right, sir, I’ll just park my kit in the Mess, and I’ll be back”. I make my presence known in the Mess, dump my kit on a bed in a standard army bell tent, whose sides have been rolled up to increase the oven like ventilation, and return to the major. There I find he has already removed all the seats from the Beaver, except mine. In their place he has squeezed in a very large tyre, like a tractor tyre, and surrounded it with an assortment of other gear. Immediately my brain throws the words ‘Weight’ and ‘Concern’ into my mind. Exasperated at not being consulted I ask the major, ”How much does all that weigh?”. If he notices I haven’t used ‘sir’, he doesn’t remark on it. And he can only give me a vague estimate of the total weight. “Well, sir, there’s too much gear on that aircraft. Without going into a lot of detail, over-loading it can result in a nasty accident. My Squadron commander has invested me with the captaincy of, and responsibility for this aircraft. If anything goes wrong I get it in the neck twice: once when it crashes and again at the court of enquiry. In future, I need to see the gear on the ground to assess its weight, before it’s loaded”. I place considerable emphasis on the last three words. I could see this ‘mouthful’ had stuck in the major’s craw and upset his digestion. Sergeants do not give orders to majors: it’s majors that order sergeants around. However, he said nothing and that was as good as “Sorry”. Now I had to sort out this problem. I was reasonably satisfied the A.U.W. would be within limits if I removed most of the other kit. So I got airborne and climbed to 6000 feet. Under normal circumstances I could easily get through the pass to Ain at 4500 feet, but I’m going to do a stall check just to set my mind at rest. Normally a fully loaded Beaver with landing flap and no fuel in the tip tanks stalls at around 44 knots. This time it does so at 50 knots, and there isn’t that much fuel in the tanks either, so that tyre weighs a bit more than I thought. I mentally remember and thank those Army Air Corps (A.A.C.) instructors who taught me theory and practice, but more importantly, how to use that knowledge. On to Ain, and with a curving approach I settle on 60 knots as my ‘finals’ speed. Sure enough, ‘she’ sits down promptly soon after the ‘round-out’ and only moderate braking is needed because Ain is uphill. I supervise the removal of the tyre because I don’t want any parts of the Beaver inadvertently removed with it. Now back to Beihan, to load up the gear I rejected on the first flight. The second ‘trip’ also includes a range of other accoutrements the major has selected for Ain. But they’re all on the ground and none of the major’s staff are making any attempt to load them. Good, the message has got through. Satisfied all of it can go, I show the soldiers where I want each piece stowed. Then it’s off to Ain again. With no weight problems this time, it’s straight across the pass, but I give myself enough height to be safe from any turbulence caused by hot up draughts or down draughts coming over the top of the mountains. Then swing left, do the checks, lower flap, get the speed back and make every effort to complete a smooth landing. On the way back I don’t go through the pass. Instead I make a detour to another ‘strip’ by following the border north to the end of the mountains, and then turning east to meet up with wadi Beihan. At this point, it too, has passed the end of the mountains to disappear into the beginning of what eventually becomes the Saudi Arabian Empty Quarter. On the western side of the wadi is an airstrip called Timna. Well, a sort of airstrip, for there are no markings and the surface is sand. I’m landing here because shortly before David Ashley left for Some weeks later the subject of the jade figure arose in the crew room. David seemed to think it could be part of the Queen of

There are four of us in the Mess this evening: the Regimental Quartermaster Sergeant (R.Q.M.S.), a medic sergeant in the R.A.F., a Lancer sergeant, and myself. While we stand there supping our beers a Camel spider makes a brief appearance in one corner of the tent. It takes only seconds for it to race, upside down, across the tent top and disappear out of sight. They’re about three to four inches across the legs with a mottled, sandy brown body. They sport a nasty bite: if unlucky enough to be bitten, it’s a trip to the hospital. In the middle of the night I am awakened by an electric storm. The lightning is almost continuous and so bright it’s like daylight for brief periods. The storm persists for about an hour and then goes away. But there’s no rain, not a drop. With difficulty I get back to sleep, but within minutes – or so it seems – I’m being awoken by the ‘bearer’ bringing my morning mug of tea. After breakfast I go out to the aircraft to check with the mechanics as to its health and am reassured to hear good news. I did not expect hear anything else, for Beavers are, on the whole, very reliable. One of the F.R.A. officers wants to make a ‘recce’ along the border in about an hour, so the day starts slowly, just how I like it. When we set off I do the ‘recce’ at 300 feet above the ground to give us a close look, but this means flying close to the towering ridge of rock to our right as we go north. We see there is more and more movement of troops over the border and a build up of the Royalists supplies. So far, though, there have been no incursions to our side, for we are still flying in their supporters. When satisfied he has seen enough I go back the long way instead of through the pass. In the afternoon I take another officer and two soldiers to Ain, and follow that with a supply flight, also to Ain. It’s now Friday and the pattern of flights has been much the same every day, the only change is the temperature: it just keeps on getting hotter. Today it’s even more noticeable. When I take off at Tonight, while standing in the mess again, the R.A.F. Medic sergeant tells us about an experience he had a couple of weeks ago. As an act of humanity he goes to the village each day to tend any sick villagers, who accept him as a doctor. The authorities are agreeable to this, for they see it as means of gaining the hearts and minds of the locals. One day he is approached by an Arab man who explains his wife is ill. As they walk to the Arab’s hut ‘Doc’ asks what the problem is. “She’s got this wound in her side”, he says. “Well, let’s take a look at her, then”, says ‘Doc’. “Oh no, you can’t see her; that’s not permitted”. She’s in purdah, the total body covering worn by Arab women to prevent a married woman being seen by men or strangers. “Look, unless I see the wound I can’t diagnose what’s wrong and suggest a remedy”, says ‘Doc’. The two of them stand and argue for a few minutes, but eventually the Arab relents and shows ‘Doc’ into another ‘room’ where his wife is laid on a very rudimentary bed. The Arab gabbles to his wife, gesturing with his hand she should turn over. In considerable pain, she does so and pulls her robe to one side. In the dim light ‘Doc’ sees she has a deep, septic wound some three inches long and an inch wide. She is listless and her skin is hot and tight. It’s clear to ‘Doc’ he can do little for her. What she needs is a surgeon with drugs that ‘Doc’ does not have in a hospital. “You need to get your wife down to the “Queen Elizabeth” hospital in “ “I see” says the Arab, in a very worried voice, “How long will she have to be there?”. ‘Doc’ thinks for a moment, and then says, “Oh, about six weeks, I should think”. They leave the room. Outside the Arab stands there, deep in thought. It then becomes obvious he is calculating the cost of the return airfare on an Aden Airways DC3, the surgeon’s fees, and the costs of the stay in hospital. He turns to ‘Doc’ and says, “Forget it, I can another wife for less than that”. ‘Doc’ is dumfounded by this callous attitude and pleads with the Arab to reconsider, but he will not. Sadly, the woman died ten days later. Some Arabs still believe women are ‘belongings’, to do with as they see fit. Life can be very cheap here. Months later it’s my turn to be at Beihan again. Nothing much has changed at the camp, though little ‘luxuries’ have appeared: for instance, a shower. It’s simple: just fill the overhead tank with warm water and pull the string when ready, but make sure you’ve got your soap ready. The political situation has changed little. Beyond the border the Royalists have held their position, but a break out through the Republican positions appears very unlikely. For a couple of days the routine is much the same as before: recces, supply runs and liaison trips. Then on Monday I’m asked to take two innocuous looking wooden boxes to Ain. They are approximately 45 cm (18 ins) long, about 25 cm (10 ins) deep and around 10 cm (4 ins) high, and they are strongly made. They might look innocuous, but I find they are extremely heavy for their size. As I load one I ask the major – he of the tyre incident – “What’s in these, sir?” For a moment he hesitates. I can see him thinking; “Do I, or not, reveal the contents to this man?” Then he says, ”They’re full of Maria Theresa Dollars” ( My face must have been blank and betrayed my ignorance, for he immediately followed with, “They’re silver coins”. “What are they used for?”, I ask. “Oh, um … we pay the Arab soldiers with them”. I reply, “Oh… yes”, and pick up the other box. But I’m far from convinced with his glib answer. I cannot believe Arab soldiers are paid in sliver coins: if they’re solid silver, its value is too much to be an Arab soldier’s weekly wage and too little to be his yearly salary. And why pay wages here where there’s nowhere to spend it? As I take off I conclude, rightly or wrongly, this money is not for the Arab soldiers. Instead, my mind reasons it is going across the border to fund the Royalist cause. I wonder if there’ll be any questions “in the House” about this. Through the pass at a safe height to Ain and the usual curved approach to ensure I don’t cross the border. After landing I’m sorry to see all that money being taken away. And, although I read the newspapers for the next few weeks, I don’t see any articles in the press about it. Maria Theresa Dollars (Thalers or Talers) were first minted in 1742. As its name implies they were named after the Empress Maria Theresa who ruled the Austrian-Hungarian empire from 1740 to 1780. Between 1751 and 2000 it is estimated some 800 million were produced by a number of mint, all with the date 1740. Being one of the first coins used in the They are 40 mm (1.57 ins) in diameter; 2.5 mm (0.1 ins) thick, weigh just over 28 grams (1 ounce) and are 83.3% silver. It became the favoured currency in the Since that day I have conservatively estimated the value of those two boxes. In doing so I have assumed a relatively higher exchange rate with the pound in 1963 than is the case now, reasoning based on its importance and more widespread use then. At that time I believe one

Some weeks later I am at Beihan, yet again. If I think I’m having it rough, I give thanks I’m not one of the garrison or the R.A.F. Medic sergeant, for they are here for the duration. That night as we stand in the Mess discussing a range of disconnected subjects, I hear and remark on the sound of distant machine gunfire. “Oh, that’s alright”, says the R.Q.M.S., “it’s the two Arab soldiers I sent out to get rid of the ‘Pie-Eye’ dogs that keep on raiding my Ration Store”. As we resume drinking and talking the gunfire starts again. The familiar chatter of I have watched and been involved in all manner drill movements, but never have I seen the ‘ground-zero horizontal position’ performed faster than the ‘synchronised sergeants’ making the Mess floor in record time. Thursday dawns after three days of routine flying. Still the Yemenis are fighting it out over the border, though it is now obvious the Republicans will ultimately win and take power. Meanwhile we continue to shuttle equipment and bodies back and forth from Ain, and do recces along the border. While flying a Lancer officer on a recce north from Ain, close to and low along the border, I notice the windscreen is becoming smeary. At first it does not register, but soon I know there is oil leaking from around the propeller and expel the words, “Damn, the bloody oil seal has gone”. I tell my passenger why we must return to Beihan, but he doesn’t see understand the urgency and wants to see more. I ignore him and do a 180° turn at the northern end of the mountains, put the propeller into fine pitch and, much to the Lancer’s annoyance, start climbing for sufficient height to get through the pass. By the time we turn east to enter the pass the screen is already becoming streaked with oil. Fortunately, in this heat we always fly with the windows open, so I can lean to the left to get a better view. Unbeknown to me I am acquiring the complexion of a ‘rough-neck’ on an oil derrick, as hot oil spray borne on the slipstream curls round the window into my face. Now we’re over the propeller remain in fine pitch for landing? “Sod it”, I mutter to myself, “ I can’t remember whether oil pressure or the weights maintain fine pitch”. I stop worrying when I realise I can do nothing about it anyway. I decide it’s got to be a straight in approach and carry out the Downwind checks. Visibility through the screen is poor and I can only see clearly sideways. Flap down, speed back to 60 knots and I can just make out where the runway is. Luckily the runway is long, so I ease ‘her’ down slowly, using the edge of the runway as my reference for height and direction. I use a lot of the runway and it’s not the best landing I have ever made, but we’re down in one piece. I poke my head out of the window to taxi ‘her’ back to dispersal. On jumping down I exclaim, “Heaven’s ‘she’ looks a mess”. As ‘she’ will not be ready for flight again before my detachment is up, it’s the end of my week in Beihan. It’s back to civilisation for me. Next episode: The Modern Mariner, but still “Water, water everywhere and not a drop to drink”. |

|

Chapter 8. Abandon Aircraft and Catching a Carrier. We, the pilots in 15 Flight in 653 Squadron, have just completed a rehearsal on how to abandon a Beaver over the sea. It is a training exercise that we repeat periodically to ensure we are prepared for such an eventuality. But this one is particularly important for two reasons. First, because in one particular situation it is a complex procedure, and secondly, we have received a signal from H.Q. instructing us we will be carrying out deck landings on a Royal Navy (R.N.) aircraft carrier, weather permitting. So we have just done several dry runs, each of us, in turn, changing roles to ensure all now know “the ropes”. There are two scenarios that we practice: The first covers a flight where passengers are being carried. It is a relatively simple procedure, but in some respects more dangerous than the second. In this case we have to assume most, if not all of the passengers cannot use a parachute, and there will not be time to teach them before the flight begins. Thus they are given a Life Saving Jacket (LSJ) and tuition on how and when to inflate it, but no parachute. We, too, will carry a LSJ, and also a seat mounted, single man, dinghy. Depending on the number of passengers we may be able to cram in another, bigger dinghy. In this scenario it is assumed the pilot will be able to glide the aircraft and ditch in the sea. If there is a strong wind blowing, we will land along the waves, not into wind: if the waves are not too high, we will land into wind. And it is this act of ditching that is dangerous. Putting a Beaver down on the sea is, to say the least, difficult, because of its fixed undercarriage. No matter how slow one makes the approach, water is like concrete at that speed. Those wheels dig into the sea, decelerate very rapidly and the kinetic energy stored in the aircraft causes it to tip up violently, possibly even somersault over. Not a good start. Even if you have tightened up your four-point harness the forces will be excessive, and those in seats with only a lap strap will suffer even more. Disorientated, maybe upside down, in an aircraft fast filling with water is not the best way to begin sea survival. There are two schools of thought on how to minimise the somersaulting effect. Some pilots postulate side slipping a wing into the sea at the last moment to lessen the tip up effect. Others favour the low speed, low tail approach, and a deliberate stall at the last second. Both are supposed to cause the aircraft to drop, right way up, into the sea. It is thought the wings will then act as flotation chambers long enough for the inflation of dinghy(s) and evacuation. Either way I think it comes down to, “You pays your money and takes your chance”. The second scenario is where the only person aboard is the pilot and is an entirely different the situation. In this case we will abandon the aircraft by parachute to avoid the ‘tip-up’ effect of ditching. In fact whenever the flight is single pilot, he must wear a back parachute in addition to a LSJ and a dinghy. However, this makes evacuation of the aircraft far from straightforward, for having donned this cumbersome equipment the pilot’s bulky form makes it physically impossible for him to get out of the Beaver narrow pilot’s door. To overcome this problem we have adopted the following procedure. First of all, another person is taken on the flight. Ideally this is another pilot or mechanic, someone who will wear and have been trained in the same survival kit as the pilot. As an aside, this means a maximum of four passengers can be picked up at the destination. The flight is to be made at no lower than 5000 feet. This is reckoned to be the minimum height to give adequate time to abandon the aircraft. Imagine a serious condition is encountered, such as engine failure, the first thing the pilot does, an almost reflex action, is to set the Beaver in a glide. He then carries out a series of remedial actions to establish the cause, in the hope the engine can be restarted. While the pilot is engaged doing these, the co-pilot clambers over his seat. There he will be ready, if the pilot confirms the emergency, to open and jettison a cabin door and throw out the seat next to it. His last action before jumping out and parachuting into the sea is to jettison the co-pilot’s seat – the one he was sitting in. While this is going on the pilot trims the Beaver slightly nose down, makes sure all services are off, undoes his straps and then follows his co-pilot out of the cabin, parachuting down to join his comrade. When parachuting into the sea it is advisable to release the ‘chute before entering the sea, but this requires fine judgment. Three factors must be borne in mind. First, if release is made too early the drop will be too high and one goes a long way down before inflation of the jacket takes effect. Second, the gas bottle that inflates the LSJ must not be operated above the water, otherwise the collar of the jacket hitting the water can break one’s neck. Third, if the parachute is released too low, it is possible to come up underneath it on returning to the surface. Getting out of this is not easy, and in some cases in the past has resulted in suffocation. Luck is no alternative to having good instructors, ground crew, mechanics and technicians who are dedicated to maintaining the highest standards of flying, servicing and maintenance, then the odds of having to take to a ‘chute or ditch are extremely low. Having satisfactorily completed the emergency drills, we are now ready for the second exercise: to practice deck landings on H.M.S. Victorious. These will take place in about ten days, depending on the progress Victorious makes to the Some eight days have now passed and our Flight commander, Alan Parker, has just finished briefing us on deck landings. He has explained what changes we need to make to our normal circuit and approach to compensate for the movement of the carrier. Unlike Navy pilots, who have special “decks” built on R.N. air stations to hone these skills, we have no way of practicing those changes before the day, all we can do is spend some time during the next couple of days perfecting our short landing skills. We are at a disadvantage compared to them.